Jeffrey Schiff

Deux Ex Machina

Recent Work

Installations

Public Commissions

Sculpture

Performance & Interactivity

Drawings & Photoworks

Early Work

5 of 6

![]()

![]() Return to Installations

Return to Installations

Collection of Williams College Museum of Art

Year: 1989

Materials: limestone, wood, and steel

Dimensions: 12' x 10 1/2' x 8 1/2'

Grinder

A hand-operated grinding mechanism is clamped to one of the Ionic columns of the Rotunda. The grinder rests on a large block of limestone supported by a wood frame. A steel extension arm connects the grinder to a 24' tall, tapered pointer, which is anchored to the center of the floor and rises into the dome. When the surface of the stone is ground, the action propels the pointer, magnifying the movements into the space of the dome.

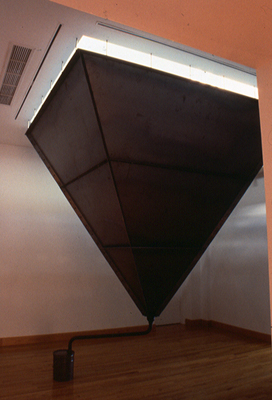

Funnel

In this rectangular room a central skylight floods the contained space with light. A funnel mounted directly under the skylight captures the light before it can diffuse into the room, and channels it into a sealed 5-gallon steel drum.

WILLIAMS COLLEGE MUSEUM OF ART

October 1, 1988-April 9, 1989

Jeffrey Schiff's installation for the Williams College Museum of Art, Deus Ex Machina, consists of two site-specific sculptures for adjoining galleries on the Museum's top floor. Both galleries are on the central axis that runs through this floor of the Museum: the Aaron Gallery is a rectangular room dominated by its central skylight; the rotunda or Faison Gallery is a symmetrical octagon in the form of a classical temple with a 30-foot-high domed ceiling supported by eight Ionic columns. The rotunda is the original museum structure, built as the College's first library in 1847.

On first viewing, the two sculptures may seem to have little in common. In the Aaron Gallery Schiff has created a form resembling a funnel which encloses the skylight, containing and metaphorically channeling its light into a closed steel drum. In the rotunda a tall pointed pole anchored at the center of the floor rises into the dome. The pointer is also connected to a grinding mechanism which is attached, in turn, to of the rotunda's columns. The grinding mechanism rests on a large stone block supported by a wood frame. When the artist grinds the surface of the stone, the grinding action also moves the pointer which probes the space of the dome above.

In spite of their formal differences, both sculptures perform visual and phenomenal actions which are simultaneously in opposition and in harmony with one another. The work in the Aaron Gallery takes the diffuse light of the skylight and directs it downward in a specific container. Schiff explains that "light is given freely and relentlessly-without discrimination or mercy. This piece involves the attempt to transform this ethereal substance from above into something collectable and transmutable as a material substance on earth." The sculpture in the rotunda takes a specific human action-the circular grinding of a stone-and directs the result of this action upwards to the symbolically infinite space of the rotunda's dome. In Schiff's words, "I am addressing the rotunda as a classical temple, commenting on the cultural orientation of classicism. Classicism attempts to resolve basic universal oppositions: earth/heaven; chaos/order; the finite realities of material existence/the speculative possibilities of the spirit and the imagination. It does so through the creation from chaotic, earthly materials of structures that embody abstract, universal laws. The laws that are at work in the heavens are manifested in the forms of the classical temple-the circular plan, the Ionic columns, and the hemispherical dome. The enterprise of classicism is based on this interaction of the experience of our bodies in the mud with our capacity for imagination, speculation, and spiritual aspiration.

"I am 'occupying' the site of the temple to expose and interpret these relationships, My sculpture operates in its context in the same way as does the bridge in Heidegger's quotation:

The bridge swings over the stream with ease and power. It does not just connect banks that are already there. The banks emerge as banks only as the bridge crosses the stream. The bridge designedly causes them to lie across from each other. One side is set off against the other by the bridge.

In this way the sculpture reinterprets and reactivates its site. It restores the classical temple from a somnolent, historicist anachronism to an actively functioning temple. In this temple human labor probes the heavens. The direct experience of labor-of the body under stress, of materials in friction-is directly linked to human projections on universal order."

Far more than a formal exercise in opposition, this installation by Schiff continues his evolution as an environmental artist and introduces new strategies, elements, and meaning that the artist has used previously only in discrete sculptural objects.

Schiff first gained recognition for his environmental installations at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), Boston, (1979); the Stux Gallery, Boston; and other sites in southern New England. At the ICA Schiff created a space within a space by rubbing graphite powder into the gallery walls, floor, and ceiling wherever these parts of the permanent structure overlapped the imaginary space Schiff was imposing. Thus the sculpture was a subset of its architectural setting, an image entirely dependent on its site, yet opposing it. The artist described himself as "a setter, assessing the topography of a place (both physical and cultural) and building accordingly a structure inseparable from its context. This interactive relationship to site is analogous to any succession of cultures, such as the Roman occupation of Etruscan sites or the Italian Baroque transformation of pagan temple ruins into Christian churches." In subsequent works in which Schiff built rather than drew spaces into sites, it is the interaction between the site and his addition that is the focus of the work.

After a trip to Japan in 1985, Schiff completed High Mesa, an installation for the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University. In addition to "recasting the gallery in terms of landscape components," the installation combined reverences to traditional Japanese floor-oriented domestic architecture with Schiff's notion of an idealized habitat for an artist. Each of the dwelling's architectural features provided an artistic/psychological function: "the entry, a means of elevating from the natural state to that of artifice; the hearth, a place to transform materials; the bed/platform, a setting from which to contemplate the world outside oneself; and the well at the precipice, a more terrifying place where one can plumb one's own depths."

Such layering of meaning and form plays an important role in both the artist's site-conditioned works and his independent sculptures. Since 1984 Schiff has created a group of sculptures that join abstract blocks of granite with functionally suggestive concrete forms such as handles, as in Possession (Iron) (1985) and Possession (Dam) (1985). The artist's granite and concrete works also reflect an Asian influence-that of Chinese ceremonial bronze vessels, which were prized by the Chinese during the Bronze Age because of their importance in ritual ceremonies. Schiff's granite and concrete sculptures and the installations at WCMA also reflect a form of ceremony-a ceremony of physical/mechanical work.

Schiff communicates the ceremonial nature of work though his use of industrial materials, moving mechanical parts that can perform a task, and shapes (most often handles) that suggest utility. In one sculpture, Opening Up (1987), the artist grinds and enlarges a hole in a slab of concrete by moving a cylindrical handle in a slow and methodical movement around the inside of the hole. His deliberate and painstaking method and the depth of his engagement are ritualistic and meditative, and they recall a time when physical work was more truly experienced and valued. This view of labor also relates to other forms of Eastern thought and religion-the karma of work, for instance, which is one philosophy of Buddhism that promotes reverent and steadfast work as a path to enlightenment.

Jeffrey Schiff demonstrates his reverence for work in the very manner his installation and objects are made. The works are meticulously crafted by the artist and by the fabricators he engages. When asked about his selection of craftsmen, the artist related his experience with the metal fabricator in California he employed to make Vat, 1987. Midway through their interview, the craftsman began correctly completing the artist's sentences, and he was hired on the spot.

Schiff's use of metal and other industrial materials and the form of his new work relates to the Italian Arte Póvera (poor art) artists, who since the late 1960s have used new and cast-off industrial materials to make an art in opposition to the slickness of "high-tech" commodities of the late 20th century. While Arte Póvera artists assign to their use of industrial materials looser, more expansive meanings than Schiff, his work is perhaps more readable as a result of his layering of specific points of reference and suggested psychological meanings. A group of works from 1987 and 1988 that include padlocks illustrate this point. Each of the works joins two or more distinct materials through the use of a padlock. The padlocks not only lock the materials together "to produce certain physical and emotional responses," but also invite us to consider the results of releasing the lock and thereby discern the meaning of each form and material individually. The padlock works characterize Schiff's work of the past two years: "the overt references are industrial/mechanical, but the undercurrent is psychological."

Finally, Schiff's projects for outdoor public spaces provide insight into his motivation and intentions. Recently the artist has been engaged in the design and supervision of public environmental projects for Charlestown, Massachusetts, and Baltimore, Maryland. In both cases the artist, while creating communal spaces in urban environments that involve automobile and pedestrian traffic, "is attempting to construe our mundane, functional activities as more meaningful acts––to allow the act of crossing a street in Baltimore or meeting someone in central Charlestown to be seen as an enduring, archetypal act."

Jeffrey Schiff combines a sense of social responsibility with a clear aesthetic program. Whether he is making temporary environmental sculptures for gallery spaces or permanent structures for public spaces, Schiff reflects many of the sensibilities for which other artist must rely on the expertise of architects and landscape architects. His desire to make his art accessible and human without compromising aesthetic integrity or sacrificing spiritual intensity places him among other American artists of the late twentieth century who share a sensitivity to place and perception and an interest in communicating a wide range of social, political, and psychological concerns.

W. Rod Faulds

Acting Director

NOTE:

Quotations in the essay were taken from conversations with Jeffrey Schiff and letters from him to the author dated July 8, 1988 and July 13, 1988.